Home delivery provides weekend meals plus personal connection

May 19, 2021

School’s social worker’s commitment to at-risk students offers continuum of care

As you drive south on Route 1 from New Castle County to the beach resort communities of Lewes and Rehoboth Beach, there’s a sense of moving toward a paradise where life is easy: fine dining destinations, upscale shopping, and endless entertainment. Luxury vehicles clog the road leading to vacations and leisure.

However, hidden behind the obvious signs associated with a comfortable lifestyle is a harsh reality: the faces of rural poverty. West of Route 1, tucked behind and between new well-groomed neighborhoods, mostly down rutted unpaved lanes, the ramshackle signs of poverty emerge. Abandoned couches and vehicles, doors hanging on hinges, and homes with rotting roofs and broken windows replace manicured landscaping and refreshing pools. These crowded Sussex County neighborhoods appear to have developed as pop-up communities rather than the surveyed building lots surrounding them.

BACKPACKS HELP

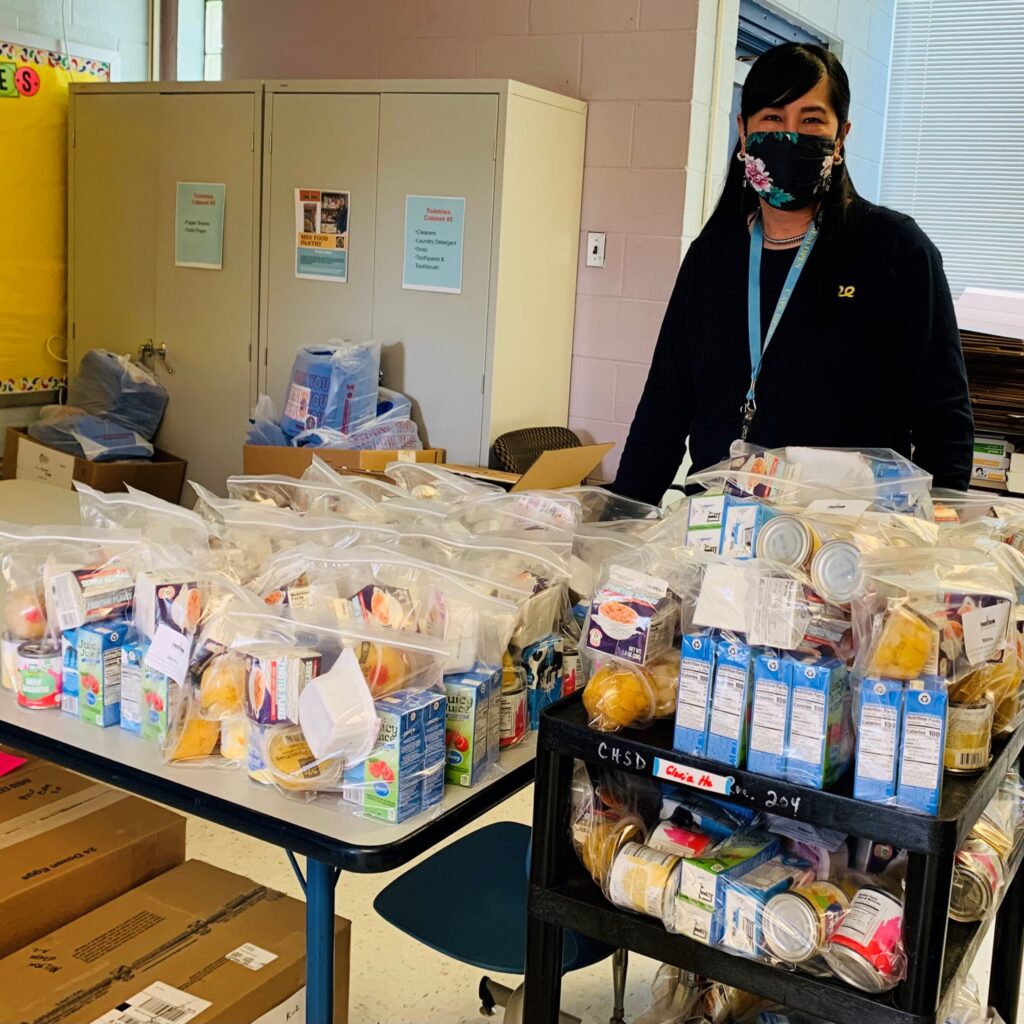

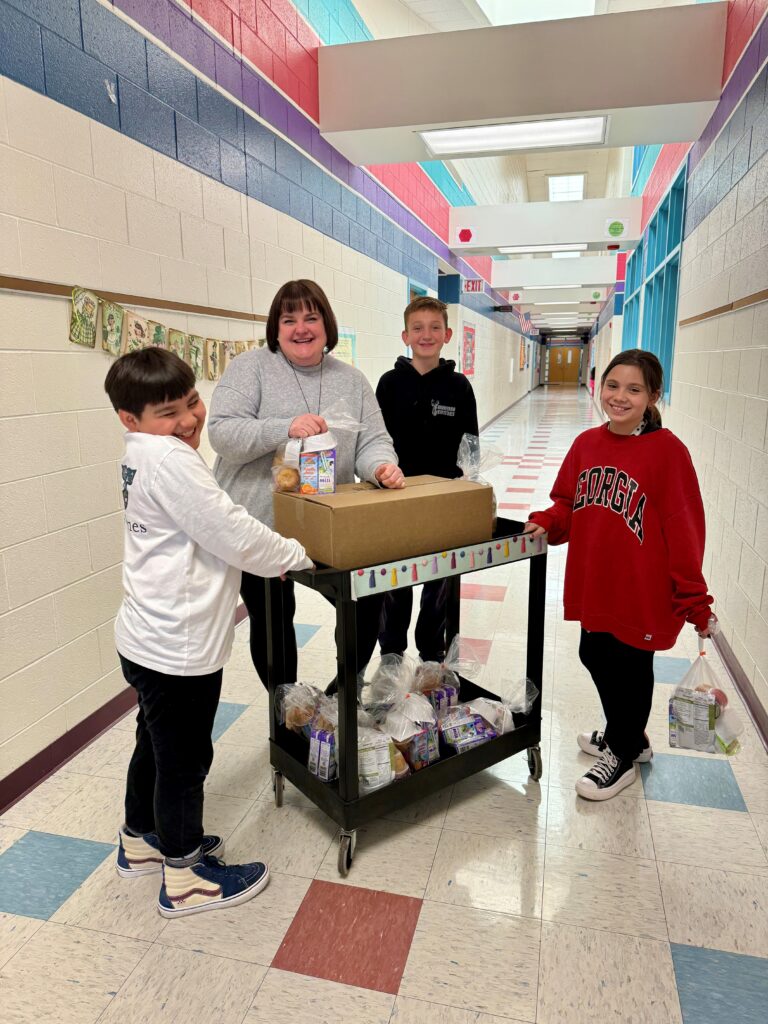

Perhaps no one is more familiar with the impact of an impoverished home – or the lack of food and shelter — than Milton Elementary School’s social worker, Gloria Ho. For years, Ho has managed the Food Bank of Delaware’s Backpack Program and Harry K Foundation-sponsored Food Pantry at her school. The backpack program provides children with basic weekend meals. Each clear plastic bag contains nutritionally-balanced meals. Backpacks are stocked with kid-friendly, nutritious food including shelf-stable milk and juice, meals such as macaroni and cheese, spaghetti and meatballs and beef stew, granola bars, apple sauce, cereal and more.

They are packed by volunteers, and typically distributed at the school, placed discreetly in students’ backpacks. In 2020, we distributed more than 181,000 bags through the program.

PANDEMIC MODE: HOME DELIVERY

Ho delivers these small bags of weekend meals to students whose parents opted for remote – instead of in-person, in-school – learning, parents who lack transportation or the means to pick up the backpacks during school hours.

“It’s mostly a matter of organization,” Ho says, double checking to make sure she’s got her maps as a GPS backup and a checklist secured to a clipboard. The backseat of her SUV is packed with the weekend meals, some clothing for one child who’s outgrowing her own, and the bonus art activity packs donated by a partnership between the Food Bank of Delaware and the Freeman Arts Pavilion Sussex County. Elementary and middle school students received a Creative Nourishment Kit along with their Backpack meals once a month during March, April and May.

The art kits contain an instructional worksheet in both English and Spanish, plus the supplies – art paper, markers, and a glue stick — as well as string for display. The project itself was created by local artist John Donato specifically for grade clusters to align with school curriculum and to encourage creativity. Just as Food Bank volunteers assemble backpack meals for students, Freeman Arts volunteers assembled 25,000 art kits for students in five Sussex County school districts.

FROM SCHOOL THROUGH POOR NEIGHBORHOODS – AND BACK

The 37-mile route with 10 deliveries typically takes about an hour, Ho said.

Her first stop is at a motel near Lewes; the students here are homeless, living with their mother in this state-provided, temporary housing. “I hope things get better for them,” said Ho as she navigates into Route 1 traffic headed toward her destination. In addition to knowing that she’s providing her students with nourishment, there’s another benefit. “It’s nice to have eyes on them,” she explained. “I can remind them they need to come to Zooms.” With federal funding assistance, the Cape Henlopen School District was able to provide remote learners with electronic tablets, a mobile hot spot, and earbuds to facilitate learning; however, teachers still struggle reaching students who fail to sign in and connect to their classrooms.

When the mother failed to respond to a knock on the door, Ho, through a brief conversation with one of the motel’s cleaning staff, was able to leave two backpacks – along with a brief reminder about attendance – with one of her students before heading south.

Her next stop is another motel, but a different situation: These parents lost their home and pay to stay at this motel so their child can complete the school year. At this stop, Ho heads inside to deliver the meals to the front desk, then checks her route and punches an address into her phone’s GPS before heading north toward the Lincoln area. “These bags of food are much needed for these students; they have no way to get food from the school. Sometimes I deliver school supplies too,” she adds.

“You’ll see, the homes they live in, it’s just so unfortunate. During the pandemic, I know their basic needs weren’t being met. It’s just more stress. I wonder about the ones I don’t see. The school has more resources and support than they are getting at home,” Ho said.

She turns off Route 1 into an aging mobile home community barely visible from a rural two-lane road. While pink rhododendrons bloom in front of a home facing that road, a sharp right turn onto narrow, unpaved streets marked with hand-lettered signs take visitors, like Ho, to their destinations. The scent of marijuana permeates the air, and abandoned vehicles or unused furniture crowd the space in front of the homes, mostly single-wide, dilapidated mobile homes. Here, Ho leaves one bag on a front stoop and another on a porch where a lopsided door hangs from a single hinge.

Next, she heads toward Kings Market near Lincoln; she’s scheduled to meet a mom in the store’s parking lot. When the mom doesn’t arrive, Ho reaches for her phone to text; there’s a quick response. The mom is running about 15 minutes late. Rather than wait in the parking lot, Ho reprograms her GPS to make deliveries in the adjacent Cedar Creek neighborhood.

“I always wear my Cape shirt and my identification badge,” she said, observing a resident’s skeptical look. “A friendly smile and a wave, and most people are fine. I have been chased by dogs though,” she said. She leaves a backpack on the front steps, and heads into another part of the community. At the next home, she delivers a bag of clothing – in addition to food – to a smiling little girl. “She told me ‘I don’t have any clothes.’,” Ho said.

HOMELESS, EXCEPT FOR HER TRUCK

The last stop of the rounds: back to King’s Market. Jen, the mom (not her real name), is all smiles! Not only is she picking up weekend food for her 5th grade son, but also she reports she is happy to have started a new job as a delivery driver, pleased to have scored $11 in tips for two deliveries.

Her children have been staying with family members: Jen, who is awaiting unemployment benefits after losing her job, has been living in her truck. Since she has mechanical skills, she’s considering exploring new job opportunities in the construction trade.

Her son, she reports, is pleased with the Backpack fare. “What he doesn’t like, he gives to his sister,” she said.

Nearly two hours after she left, Ho pulls into her parking spot at school. The Food Bank of Delaware, she says, is so important to her students and their families. If it weren’t for the Backpack program, these children would not have food. For Ho, the weekly delivery route is all in a day’s work. Next on her schedule: an end-of-day meeting.

Visit www.fbd.org to learn more about the Food Bank of Delaware’s programs, including how to volunteer to pack Backpacks or make a donation to support the year-round program.