Introducing… the Produce Access Program (part 2)

March 4, 2015

Did you miss part one? Click here to read it!

By Matt Talley, Produce Access Coordinator

After my initial visit to J.G. Townsend Jr. & Co., I wasn’t quite sure exactly what the outcome would be for the Food Bank. Speaking with the frozen foods processor was one of my first attempts to cultivate a better relationship with some of the producers in Kent and Sussex Counties. The meeting in Georgetown went well – the company had made some donations to the Food Bank in the past, and they were curious to hear more about our plans for sourcing more Delaware-grown produce in the future.

Everyone knows that farmers are the ones who grow our food. But that’s only part of the story, and what I learned at J.G. Townsend gave me a lot of insight into how our food system works. You see, there’s a lot of history behind that packet of frozen vegetables that’s might be sitting in your freezer. Let’s take lima beans for an example, since that’s one of the products processed at Townsend’s facility:

A lima bean farmer probably has access to the equipment required to till the earth, plant rows of seeds, fertilize and irrigate those rows, and ensure that pests don’t completely eradicate the crop. But that same farmer may depend on another party when it comes time to actually harvest the lima beans and make them ready for market. Many farmers do not own the equipment required to harvest their crop, let alone to separate out all the leafy matter, stems and other field material picked up by the harvester. The crop then needs to be rinsed, packaged and distributed…lots of additional steps before the product is finished and ready for the market.

Due to these challenges, your typical lima bean farmer is likely to contract with a processor. This frees up the farmer to focus on farming and allows the processor to work with a number of different growers to source their raw materials – lima beans straight out of the fields! Now, there isn’t a very large window when lima beans are ready to harvest. For this reason, it’s easier to clean and freeze the beans while they’re still fresh, and then finish the process to package and distribute them after the peak harvest period. This gives the processor more time to finish producing a market-ready product when they’re not busy harvesting, cleaning, blanching and freezing the beans fresh off the field.

Here’s where things get really interesting…have you ever heard of a color sorter? No? Me either. Let’s back up a little bit. If you’ve ever had a home vegetable garden, then you’ve probably ended up with the occasional weird looking tomato, mutant strawberry or extra curly cucumber. While it doesn’t match what you would expect to find in the grocery store, there’s nothing really wrong with it. It’s still edible, it’s still nutritious, and it still tastes good.

Here’s where things get really interesting…have you ever heard of a color sorter? No? Me either. Let’s back up a little bit. If you’ve ever had a home vegetable garden, then you’ve probably ended up with the occasional weird looking tomato, mutant strawberry or extra curly cucumber. While it doesn’t match what you would expect to find in the grocery store, there’s nothing really wrong with it. It’s still edible, it’s still nutritious, and it still tastes good.

Lima beans are the same way, but in terms of color. Sometimes they come out a little bit brownish or greyish looking. A color sorter is exactly what it sounds like – a large piece of equipment that sorts items based on very exact color specifications. Grocers don’t want to carry something that looks different, so the processing industry uses color sorting to ensure uniformity of appearance in their products.

But what happens to all the rest of it? Where do the slightly brown or grey lima beans go? That’s what I was hoping to capture, a stream of perfectly fresh, good-tasting and nutritious product that never hits the market because of a slight variation in color.

The Food Bank had just purchased a vacuum sealer, and this would be the perfect test case! If the processing plant was able to donate just one or two totes, we could develop a process to repackage, vacuum seal and distribute them to families to need.

The Food Bank had just purchased a vacuum sealer, and this would be the perfect test case! If the processing plant was able to donate just one or two totes, we could develop a process to repackage, vacuum seal and distribute them to families to need.

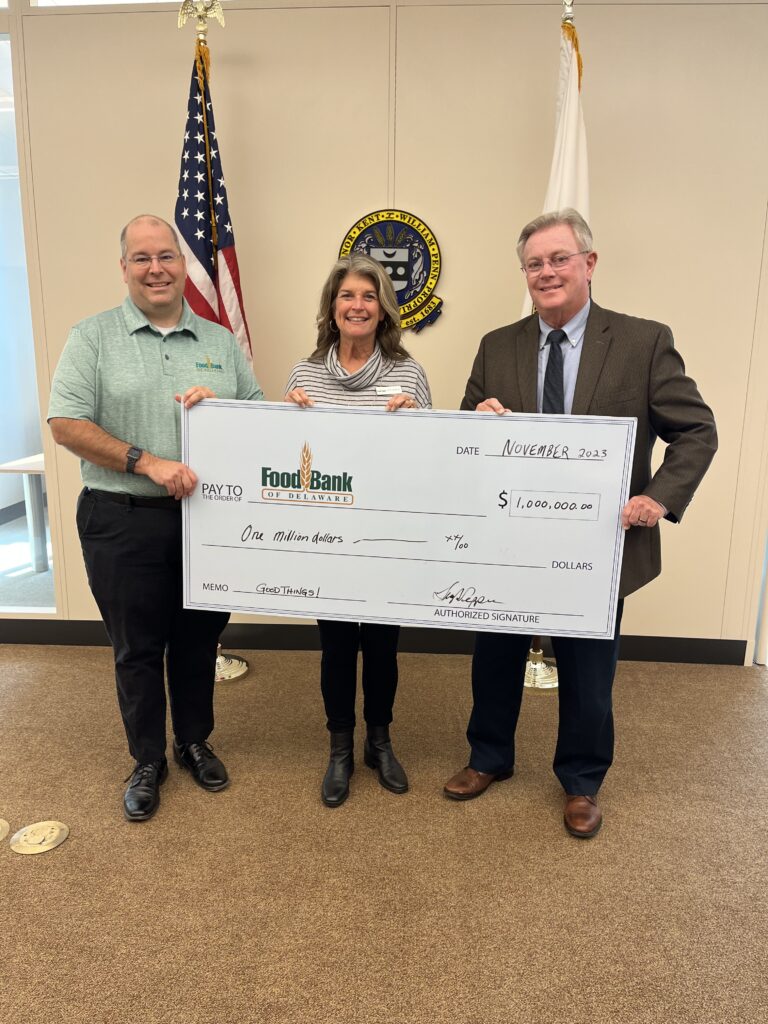

A couple of weeks after our initial meeting, I opened up my laptop and received an email that blew my mind. J.G. Townsend Jr. & Co. had conducted an inventory and wanted to donate 29 totes of black-eyed peas, green peas and lima beans. If you picture the blocks that make up the pyramids, you’ll get a rough idea of how big a tote of frozen vegetables is. Each one weighs about 1,400 pounds, so J.G. Townsend was contributing about 40,000 pounds of fresh, Delaware-grown produce to the fight against hunger!

The next morning, we sent the first of three trucks down to Georgetown to collect the donation. The totes were loaded into refrigerated box trucks to prevent the frozen vegetables from thawing out on the trip back to the Food Bank’s warehouse in Newark and then into a large commercial freezer to await the next step.

Each tote basically consists of a large cardboard box, lined with blue plastic on the inside and sitting on a wooden pallet. Since this product was never intended for market, it was never packaged. Instead, it sits loose inside the tote’s liner in bulk form. One at a time, these totes are taken to the makeshift production line in the Food Bank’s Volunteer Room, where volunteers bag up the contents in 6”x10” pouches. The bags are placed into coolers to ensure proper temperature control while they await the vacuum sealer. Once they are sealed, labels are affixed to the bags with information about the product, the Food Bank’s address and cooking instructions. Volunteers take the now finished bags and pack them into cases before they are brought back into the freezer for temporary storage.

This generous donation of produce will provide hungry Delawareans with nutritionally-rich, calorically- dense food to help them stretch their food budgets and keep their stomachs from going hungry. Unfortunately, fresh produce isn’t always easy to sell to low-income customers…even if it’s free. Nutrition education is essential to increase awareness of the health benefits associated with consuming fresh fruits and vegetables. To this end, the Food Bank’s Community Nutrition Educators seek to educate and encourage clients through onsite cooking demonstrations, handouts including recipes and preparation tips and other forms of nutritional guidance. Each package of frozen vegetables from this example will be distributed with a nutritional profile and recipes to help families to make the most out of what they receive.

In a broad sense, programs such as the Food Bank’s Produce Access Program are necessary to not only improve access, but also to help stimulate demand for produce grown in Delaware among more Delawareans. By providing supporting educational resources along with access and availability, we can help lower the risks of diet-related health concerns such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. By working with partners such as the Delaware Department of Agriculture, the Delaware Farm Bureau and the counties’ Cooperative Extensions, we can help to create more economic opportunities for the agricultural community to sell their products within the state. And with the help of community efforts such as the Delaware Urban Farm and Food Coalition and The Food Trust’s Wilmington Cornerstore Initiative, we can change the landscape of our local food economy. After all, doesn’t it just stand to reason that fresh food should be eaten where it’s grown?

In a broad sense, programs such as the Food Bank’s Produce Access Program are necessary to not only improve access, but also to help stimulate demand for produce grown in Delaware among more Delawareans. By providing supporting educational resources along with access and availability, we can help lower the risks of diet-related health concerns such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. By working with partners such as the Delaware Department of Agriculture, the Delaware Farm Bureau and the counties’ Cooperative Extensions, we can help to create more economic opportunities for the agricultural community to sell their products within the state. And with the help of community efforts such as the Delaware Urban Farm and Food Coalition and The Food Trust’s Wilmington Cornerstore Initiative, we can change the landscape of our local food economy. After all, doesn’t it just stand to reason that fresh food should be eaten where it’s grown?

If you are a farmer or producer who would like to donate to the Food Bank or for more information about the Produce Access Program, please contact Matthew Talley at (302) 292-1305 ext 249 or mtalley@fbd.org.